I. Introduction

Around the world, governments are increasingly considering different types of state action to address various forms of digital content and conduct — an approach that the Global Network Initiative (GNI) refers to broadly as “content regulation.” As they do so, many governments will look to Europe, which has carved out a reputation for taking a critical and yet rights-friendly approach to regulating new technologies. This positions the European Union’s recently inaugurated work on the Digital Services Act (DSA) to not only have a direct impact on companies doing business in Europe but to presage a broader shift in how digital content is governed globally.

This post provides an overview of recent developments related to content regulation in the European Union. It is informed by a review of several recent parliamentary reports; information published by the EU and relevant stakeholders; and recent public event and private consultations on the Digital Services Act (DSA) facilitated by GNI. These events featured participation by human rights experts from the UN and Council of Europe, members of the European Parliament (MEPs) and their staff, European Commission and Member State representatives, and other stakeholders.

As part of our broader blog series on content regulation and human rights, this post kicks off a series of contributions from GNI members and staff examining various aspects of the DSA through the lens of international human rights law. Topics that will be covered include the scope of content covered; the range of services regulated; transparency obligations; algorithmic auditing; notice-and-action frameworks; and enforcement and remedy. We hope these posts provide concrete insight and guidance that will help ensure the DSA not only respects, but enhances human rights in the EU and beyond.

II. The Road Ahead for the DSA

The DSA forms part of European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen’s broader vision for an EU digital single market. It will likely modify the longstanding E-Commerce Directive and follows on the heels of, and could be informed by and/or modify, parallel, multiyear efforts to develop more uniform European rules for data protection (encapsulated in the 2017 General Data Protection Regulation); copyright (the 2019 Copyright Directive); audio-visual media (the 2019 AVM Directive), and platform-to-business practices (2019 Regulation on promoting fairness and transparency for business users of online intermediation services). Whether the DSA results in a binding regulation, a directive providing guidance to member states, or some combination, it is likely to impact a broad range of digital activities, services, and companies well beyond EU borders.

The first step in the complicated dance of European policy making¹ was the release of three draft “own initiative reports” (OIRs) by designated rapporteur’s from each of three key committees within the European Parliament — Internal Markets and Consumer Protection (IMCO), Legal Affairs (JURI), and Civil Liberties, Justice, and Home Affairs (LIBE). These are now receiving feedback from “shadow rapporteurs” in other relevant parliamentary committees and undergoing further negotiations within the committees, with the goal of ultimately producing a unified parliamentary report to be sent to the European Commission sometime this fall.

In parallel, the Commission has published “inception impact assessments” outlining issues facing the European digital single market that the DSA should address, and opened a public consultation on the DSA. The Commission’s Directorate-General for Communications Networks, Content and Technology (DG Connect) will use both Parliamentary and public input to draft legislation, which it hopes to send to the Parliament and the European Council later this year or early next year. This will kick-off the so-called “trilogue process” of negotiations, by which these three key entities will seek to finalize and approve a final product in 2021.

III. Parliament’s Opening Moves

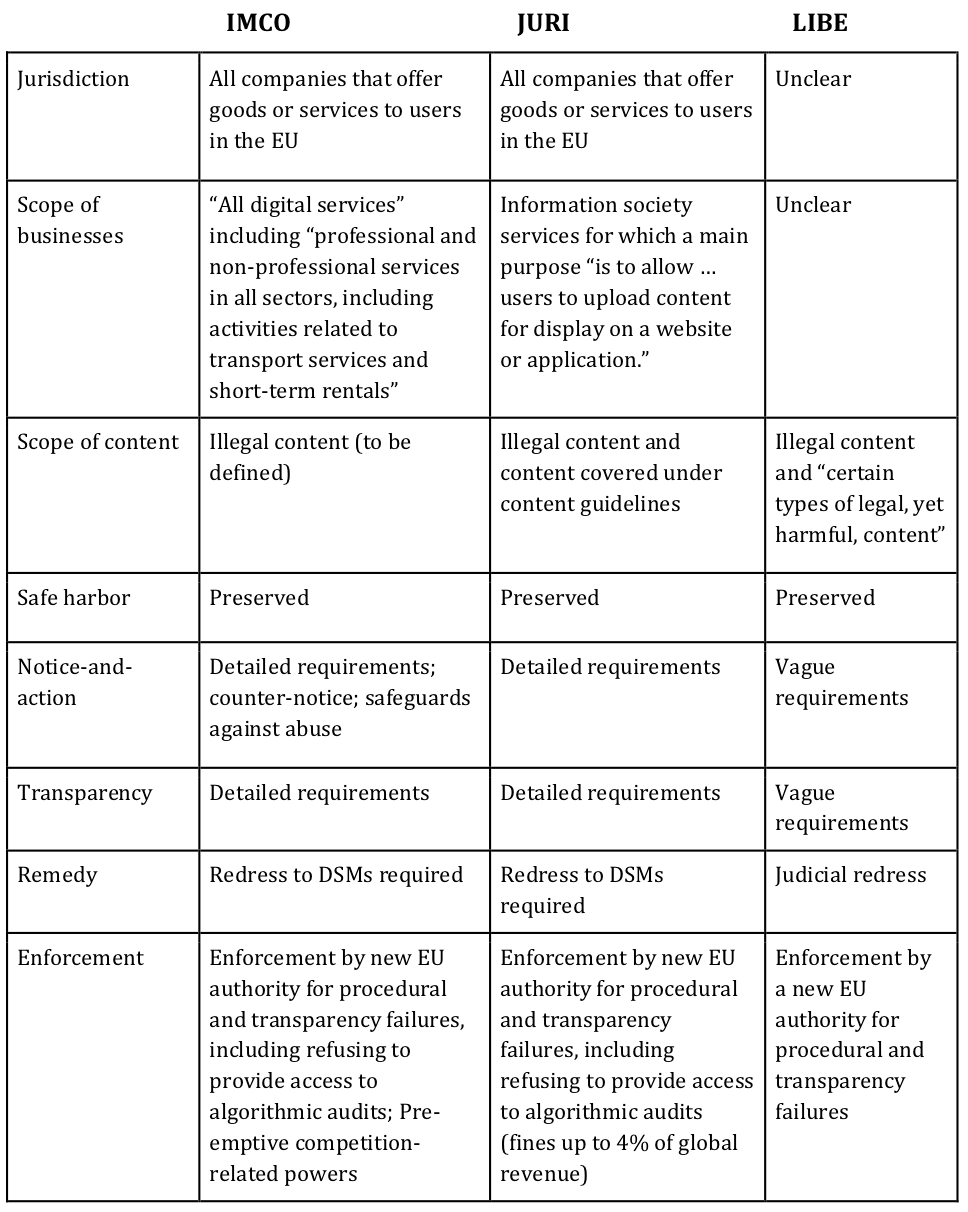

As explained in the analysis in this post, and encapsulated in the table below, the OIRs are thoughtful and demonstrate more synergy than divergence on key points. They appear to indicate a general consensus on the part of key parliamentary actors for preserving important elements of the existing E-Commerce Directive, including the principle of “safe harbor” liability protections for intermediaries and the prohibition on general monitoring obligations.

Comparing the three draft OIRs

The IMCO report was authored by MEP Alex Agius Saliba, the first-term parliamentarian from Malta representing the Progressive Alliance of Socialist & Democrats block (S&D). It is the most detailed of the three OIRs. It is the only report to focus in detail on “online marketplaces” (e-commerce platforms)³, in addition to content-hosting platforms, and to explicitly call for the DSA to cover “professional and non-professional services,” including transport and short-term rental services.⁴

At the center of this proposal are a set of “due diligence, transparency and information obligations” and a notice-and-action framework, both of which would be supervised and enforced by a new central regulatory authority working with independent enforcement bodies. The transparency and oversight commitments revolve around detailed reporting requirements, including around algorithmic transparency and auditing, and the concept of a centralized “platform scoreboard.” The report also calls for a “new framework” for transparency regarding business model-related information, such as advertising, “digital nudging,” preferential treatment, and paid search results. It also emphasizes concepts like “know your business customer,” “fair and transparent contract terms,” and “transparency-by-design/default.”

The proposed notice-and-action mechanism appears to apply strictly to “illegal content” (it calls on the DSA to clarify “what falls within the remit of the ‘illegal content’ definition”), which is a welcome departure from other regulatory approaches that attempt to also cover “harmful but legal” content.⁵ The proposal requires platforms to provide easy-to-use notification procedures, specifies uniform requirements for notices, and requires that “reasoned decisions” be disclosed to both notifiers and content uploaders, all while providing a “guarantee that notices will not automatically trigger legal liability nor should they impose any removal requirement.”

The report avoids imposing strict timelines for the removal of illegal content and otherwise appears to recognize the need for flexibility in design and application.⁶

Importantly, the IMCO report also calls for the provision of “counter-notice,” as well as safeguards to prevent abuse “by users who systematically and repeatedly and with mala fide submit wrongful or abusive notices.” Finally, the report mentions the need for out-of-court dispute settlement mechanisms (DSMs) that could provide an avenue for appealing content decisions, although it provides few details about how these would work.

While the report provides a useful sketch of some key components of a plausible notice-and-action system, there are several areas that require further elaboration or clarification. For instance, the report appears to require “name and contact details of the notice provider” in order “to ensure that notices are of a good quality,” and yet also says the system should “allow for the submission of anonymous complaints.” The report also states that content found “not illegal” should be restored, “without prejudice to the platform’s terms of service.” This would appear to imply that content should be taken down upon notification, which runs counter to the already mentioned commitment that notices will not “impose any removal requirement.”

MEP Tiemo Wölken, a German S&D MEP who has been in Parliament since 2016, is the JURI rapporteur. Given its provenance, it is not surprising that this report begins by setting out the legal justification for content regulation, stating boldly that “content hosting providers have de facto become public spaces [which] must be managed in a manner that respects fundamental rights and the civil law rights of the users.”

This report proposes that a notice-and-action system, in conjunction with access to independent DSMs, are “preferable to asking content hosting platforms to ‘step up’ and become more proactive … which could lead to … harmful effects for the exercise of fundamental rights online and the rule of law.” Like the IMCO report, the JURI report calls for the preservation of provisions in the E-Commerce Directive on safe harbor and the prohibition on general monitoring obligations, and then it goes further, taking a strong position that automated content removal results “in content removal taking place without a clear legal basis, which is in contravention of Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights.”⁷

The report frames the DSA as a regulation “on contractual rights as regards content management” and is focused on “content hosting platforms,” which are defined as information society services for which a main purpose is to allow “users to upload content for display on a website or application.” It calls for certain principles for content moderation, including non-discrimination; requires procedures for a notice-and-action system, including mandatory transparency reports and a requirement for publication of decisions to remove content;⁸ and the establishment of independent DSMs.

With respect to the notice-and-action system, the JURI report imagines this applying to a broad range of content, including alleged intellectual property infringements, which could create tension with the recently implemented E-Copyright Directive. The report avoids concrete timelines, but does call for decisions to be taken “without undue delay,” without defining that standard. It also articulates a “stay-up principle,” which makes it clear that content subject to a notice “shall remain visible until a final decision has been taken.” Finally, the report proposes that where review mechanisms exist, “the final decision of the review shall be undertaken by a human,” although exceptions would presumably be allowed for hashed content or re-uploads.

The report demonstrates considerable concerns with “user-targeted amplification of content,” which it calls “one of the most detrimental practices in the digital society.” It calls for strictly regulating targeted advertising; “clear boundaries as regards the terms for accumulation of data for the purpose of targeted advertising;” for users to have a choice whether to consent to receive targeted ads, as well as an “appropriate degree of influence over the criteria according to which content is curated and made visible for them … including the option to opt out from any content curation;” and for all sponsored ads to be published.⁹

The JURI report is the most detailed on the concept of DSMs, clarifying that they should be funded by dominant platforms and composed of independent legal experts with “jurisdiction” over compliance not just with legal and regulatory requirements but also “community guidelines.”¹⁰ It specifies that DSMs would need to be “located in the member state in which the content forming the subject of the dispute has been uploaded,” which implies that every member state will need a DSM and also, more controversially, that content uploaded outside the EU may fall outside the DSMs’ remit.

The report calls for the establishment of an EU “Agency on Content Management,” which would audit algorithms, review content hosting platforms’ compliance with the DSA on the basis of transparency reports and a public database of decisions on removals, and impose fines of up to 4% of total worldwide turnover for non-compliance. It defines non-compliance procedurally, including failure to implement the notice-and-action system; provide transparent, accessible and non-discriminatory terms and conditions; provide the Agency with access to content moderation or algorithm-related information; or submit transparency reports.

The LIBE rapporteur is MEP Kris Peeters, a first-term MEP who served until recently as the Deputy Prime Minister for Economy in Belgium and represents the European People’s Party group (center-right). Of the three reports, this is the shortest and least detailed. It states that “certain types of legal, yet harmful, content should also be addressed to ensure a fair digital ecosystem,” without clarifying what types, but otherwise seems focused primarily on ensuring that “illegal content is removed swiftly and consistently” and calling for illegal content to be “followed up by law enforcement and the judiciary.” The report underscores the need for a surgical approach to “avoid unnecessary regulatory burdens for the platforms and unnecessary and disproportionate restrictions on fundamental rights.”

Like the other reports, the LIBE report supports the prohibition against general monitoring obligations and “limited liability for content and the country of origin principle,” while also endorsing a “balanced duty-of-care approach.”¹¹ It calls generally for more transparency from platforms (as well as national authorities) and for notice-and-action mechanisms (including counter-notice), with appropriate safeguards and due process obligations “including human oversight and verification.” The report also supports the creation of an independent EU body to “exercise effective oversight of compliance with the applicable rules” (which are left unstated).

IV. Conclusion

For the most part, the three OIRs are remarkably consistent. They each aim to preserve safe harbor and the prohibition against general monitoring obligations; emphasize transparency and procedural obligations for content determinations, algorithms, and ads, including via a notice-and-action framework; demonstrate appreciation for the potential for over-removal; pay attention to the need for improved access to remedy, including through the establishment of independent, DSMs (although Peeters’ report is silent on this); and recommend enforcement (at least in part) via a new, centralized EU authority.

Just as important from a human rights perspective is what the reports choose not to propose. In preserving core components of the E-Commerce Directive while avoiding attempts to regulate the entire digital ecosystem (although Saliba’s report is less clear on this), impose strict timelines for content adjudication, require reliance on machine learning for the moderation of harmful content, or contested topics like anonymity or encryption, they provide a focused and defensible approach to content regulation.

There is much that will no doubt prove controversial and require further clarification and consideration — including rights-respecting guidance for proactive content detection and moderation (as opposed to actions taken in response to notices) and mechanisms for resolving conflicts-of-law within and outside the EU. Nonetheless, the rapporteurs have demonstrated that Parliament is likely to play a thoughtful, responsible, and sober role in the deliberations over the DSA.

GNI will continue to follow the process of amendments and negotiations that take place in Parliament and to continue to engage with parliamentarians, the Commission, and Member State representatives.

[1]The role of the European Parliament vis-à-vis the Commission in initiating and developing legislation is somewhat in flux. See, e.g., EU Parliament Briefing, “Parliament’s right of legislative initiative,” 2020.

[2] This may be due in part to internal coordination, as well as behind-the-scenes engagement by the European Commission.

[3] The report introduces the concept of “systemic operators,” which exercise “gatekeeper” roles, and calls for an ex-ante mechanism to prevent (“instead of merely remedy”) unfair market behavior by imposing remedies “in order to address market failures, without the establishment of a breach of regulatory rules.”

[4] The report introduces some confusion on this point by later by citing the need to “clarify to what extent ‘new digital services’, such as social media networks, collaborative economy services, search engines, wifi hotspots, online advertising, cloud services, content delivery networks, and domain name services fall within the scope of the Digital Services Act.” The Transportation and Tourism Committee (TRAN) response calls for further clarification of these definitions.

[5] This is reinforced vis-à-vis “misinformation” in the IMCO response to LIBE, which notes that “misinformative and harmful content is not always illegal” and calls for “an intensive dialogue between authorities and relevant stakeholders with the aim of deepening the soft law approach based on good practices such as the EU-wide Code of Practice on Disinformation, in order to further tackle misinformation.”

[6] By contrast, the Culture and Education Committee (CULT) response to IMCO calls on platforms to not only “immediately delete illegal content after positive identification, but also to continuously transmit it to the law enforcement authorities for the purpose of further prosecution, including the metadata necessary for this purpose.”

[7] It is not clear how this position, which is reiterated in the JURI Opinion in response to IMCO authored by Shadow Rapporteur Patrick Breyer, is recociled with the filtering requirement in Article 17 of the Copyright Directive, which has generated considerable controversy.

[8] As written, this would appear to exclude decisions to reject notifications and leave content up, as well as potentially decisions that fall short of removal, such as reducing opportunities for amplification or monetization.

[9] The IMCO response to JURI goes further by calling for non-EU advertisers to register in the EU so they can be held responsible for the content of their ads, and for platforms to actively monitor advertising on their services “in order to ensure they do not profit from false or misleading advertisements.”

[10] Implied here is a requirement that private companies must follow decisions by private DSMs about the application of their own content guidelines, which is without precedent, as far as I am aware.

[11] This “duty of care” concept is not elaborated upon and it is not clear if this implies the possibility of civil liability or would otherwise create tension with safe harbor.